Bringing vision into a code base

This post is about how to inject and persist architectural vision in a code base, based on a recent experience.

- High-level approach to restructure and refactor of a messy code base

- Persist architectural vision to outlive people and team changes and move the code in a single direction.

Preface: The tale of my own legacy

Some code comes with a long history and reflects the opinion and knowledge of all the people that have worked on it.

Recently I had the honor to work on a rather small, but messy code base which has been passed around between teams multiple times over the course of three years. In fact, I had worked on it myself for a while a year before and I remember very well how we were sitting in a small meeting room with stifling air, talking over the code smells and tried to come up with ideas on how to make it shine.

Due to organisational reasons, soon it was to be transferred to another team on another continent. We shared our gained understanding as best we could and explained our half-baked ideas of the next steps.

One year later this code becomes a bottleneck to the project and the assumption is that no more than two pairs are able to work on it in parallel. As an experiment we put together a team of two pairs, one from our and the other team, with the mission to make work on this code base more parallelizable - of course with on-going delivery on top.

As part of this new team the code base came back to me after over a year. The good news: The other team has made vast improvements and did an excellent job in the time given. But big parts were untouched and moreover our half-baked solutions from one year ago are now just additional complexity and became part of the problem.

It’s great to work in a small and fresh team on a single problem. The scope is narrow, which leaves our brains the energy to understand the technical details in-depth and make the right decisions on what, how and when tackle things.1 Let’s see how we deal with the actual task.

Approach the Restructuring

The initial milestone is to reach a clearly structured base, in which we can implement new changes and continue to clean up messy parts as we touch it.

We approach the refactoring in five steps:

-

Get a shared understanding of the business context

It is essential to first get a common understanding of the business domain and capabilities that the code base provides. A simplified event storming2 session helps us to get to know what we are dealing with and have a common and well-defined language to talk about the business.

Later we often have to distinguish between essential complexity, which reflects the complexity of the business capability, and accidental complexity, which is added through the chosen implementation and can be eliminated. -

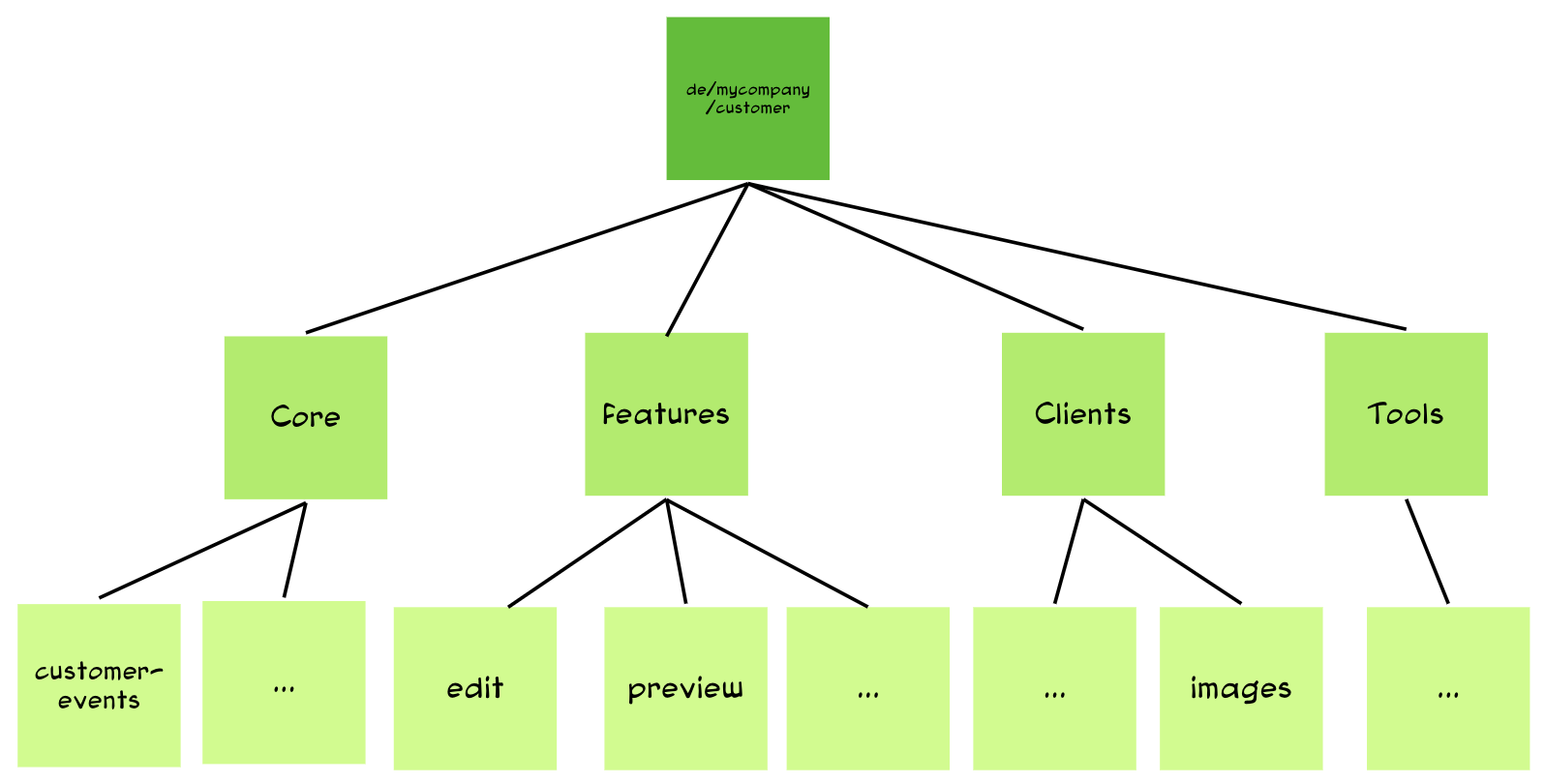

Define a high-level target structure Based on this business understanding we create a very simple first high-level structure that looks something like this.

This structure is by no means written in stone. In fact, as we proceed into the next phases, we refine it multiple times.

This structure is by no means written in stone. In fact, as we proceed into the next phases, we refine it multiple times. -

Name the mess

It is time to collect the low-hanging fruits! This means reading the code, split and move files to reach higher cohesion and rename things to reflect their semantic. The terms from the event storming session come in handy here, and the high-level target structure guides where files should live. At this point we don’t really touch any logic, but simply rename and move files, classes and (top-level) functions. Thanks to modern IDEs like Intellij, these are quite risk-free refactorings with immediate benefit. One of our measurements of success is, that a new developer should be able to intuitively navigate to the code related to a feature they are working on. In our case, a new joiner gives her subjective impression and uncovered some more unintuitive names and structures.

Example: we collect a bunch of tools, which are not directly related to business cases, like the swagger setup, in atoolspackage. ‘tools’ might not be the best name, but the important thing now is to split the mess into overseeable and obvious parts that can further worked on later.

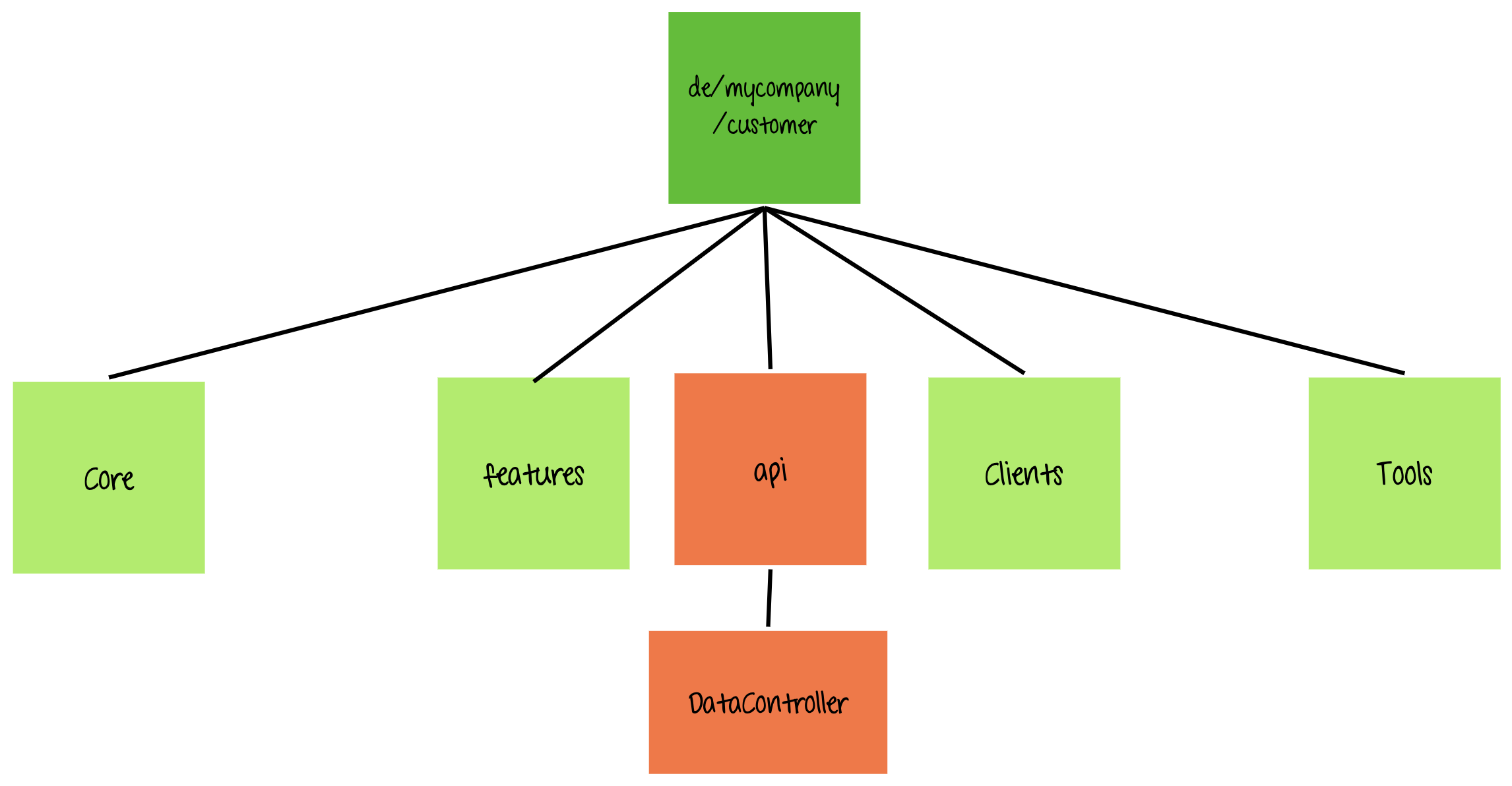

Example: The packageapicontains a classDataController. Neither “api” nor “data” says what the content of this file is about. We figure out that these are HTTP APIs for customer profile preview and editing, including image upload. We move them to corresponding feature packages. The result looks like this:

We figure out that these are HTTP APIs for customer profile preview and editing, including image upload. We move them to corresponding feature packages. The result looks like this:

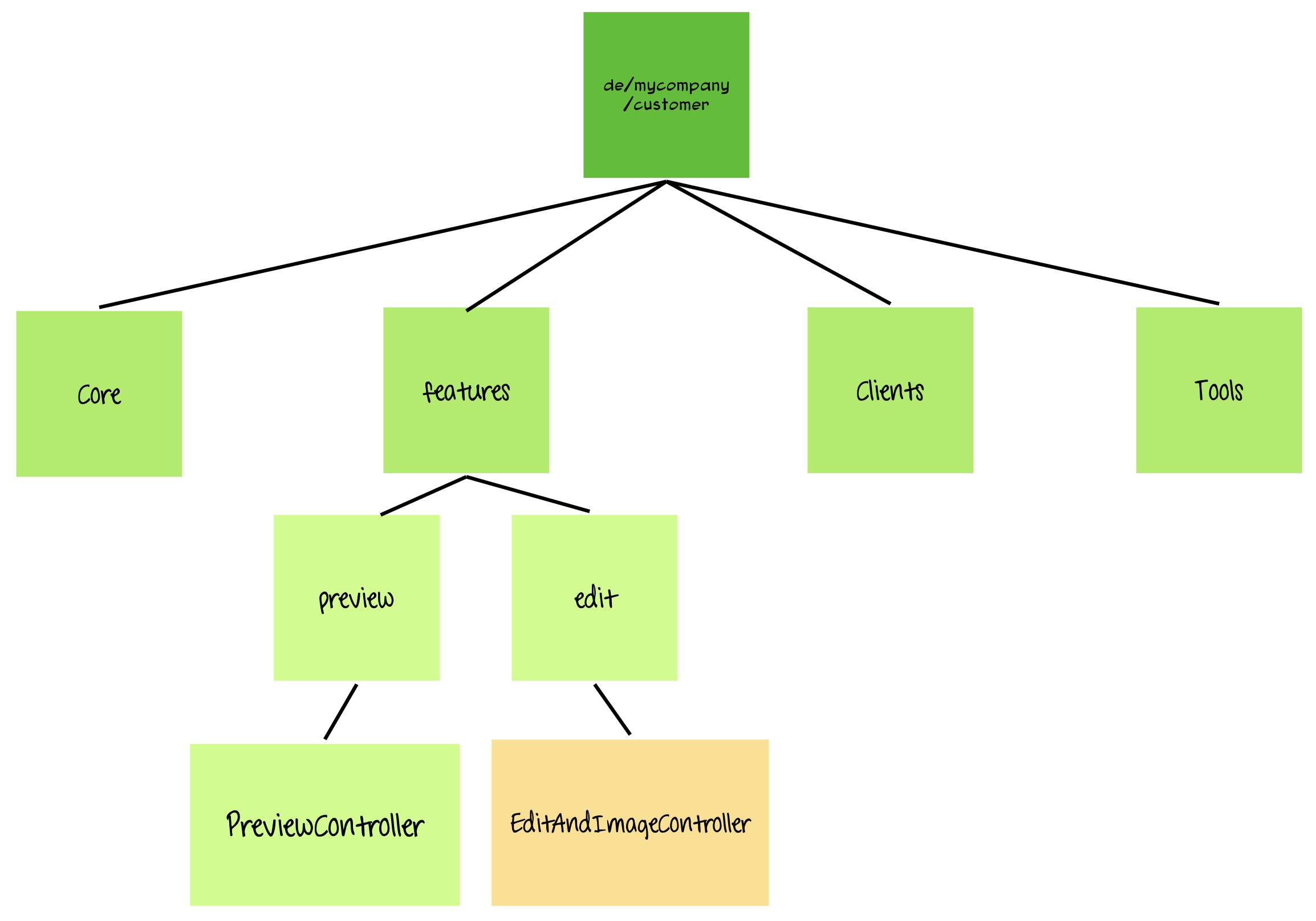

The entanglement in code is still there, maybe the

The entanglement in code is still there, maybe the previewcode uses functions from theeditcode to get the uploaded image. Maybe it would make sense to split out theimagefunctionalities and move them to the core. But in this phase, demystifying and making them obvious brings more value. The names reflect the content and are close to the right place now and we are much happier! -

Identify and prioritise the hot spots

While a lot of things are tightly coupled, we can identify hot spots that are central to the application logic and particularly complex. We identify these exploratory by using tools like dependency graphs. Some hot spots become only obvious during the feature work. Such discoveries are actually the most valuable ones, because solving them first will have an immediate impact on our feature delivery speed, which makes them cheap improvements. -

Restructure This is the most fun phase for the devs! We refactor the code to make it more understandable, maintainable and evolvable. It’s advisable to limit and coordinate the bigger tasks, as some might go deep into the fundamental structure of the application. In an ideal case we do this as part of the feature work, but since we want to significantly improve the code base in limited time, we also run refactorings as tasks on their own, so that a pair can concentrate on finding the best way. While refactoring per definition excludes changing behaviour, don’t be afraid to question existing logic. Again the question is, if this complexity is accidental or essential. One of the greatest feelings is when you spend half a day to understand what a particularly complex part is doing, just to come to the conclusion, that we don’t need it at all.

Persisting Vision

By nature the entropy, or chaos, of a code base increases with the features and changes applied on it. Therefore, refactoring should be part of everyday development work.

But changes and refactorings need to go in one direction towards a common vision on how the code base ought to look like.

A good analogy I’ve read is that “a code base should look like it’s written by a single person”3.

The easiest way to achieve this in a team is through pair programming and regular open discussions, but in fact it is shaped by any interaction and casual conversation team members have.

With larger teams this becomes increasingly difficult4 and when a code base is even passed around between teams, the communication of the vision barely happens.

So considering that this team has an expiry date, a big concern for us is how we can transfer our vision and knowledge to whoever will encounter this codebase.

The vision must be translated into the code base.

Ideally it is readable and obvious, when a developer wants to do a change, they should feel “this is how I should do it”.

But even if the code base still is a bit messy, we want to provide some guide rail and the following tools and techniques have been particularly useful.

- ArchUnit

ArchUnit is a testing framework for the architecture of a JVM based application. Our code base is in Kotlin and the framework does a wonderful job. It allows us to express our intentions in small tests that then asserts that the rule is not violated. Here is a simple example of an ArchUnit test. ArchUnit is a really amazing tool and I have yet to discover such tools for other technologies.

@ArchTest

val `classes in the core package should not use classes in the features package` =

noClasses().that().resideInAPackage("ch.chrisport.core..").should()

.dependOnClassesThat().resideInAPackage("ch.chrisport.features..")

@ArchTest

val `features should be free of circular dependencies` =

slices().matching("ch.chrisport.features.(*)..").should().beFreeOfCycles()- Manifesto / Code of Conduct

We create a Code of Conduct in the root folder of the code base, requesting any external contributor to read it before writing code. The goal of the code of conduct is to raise awareness, not explain in detail. It describes in short the business scope, the architectural goal of the code base, current state, as well as Do’s and Dont’s.

The document should be short enough for anybody to read it in just five minutes, not an extensive documentation. The points are at least mid-term, so that they don’t need to be updated every week. Some parts might be a bit more short-lived, such asDon’t write more Enzyme tests, we want to migrate to React Testing Library tests

or

Do not add more properties to the Preview class, we want to move to more specialised interfaces”.

Where possible, move such things to ArchUnit tests, where they are much more practical.

- Continuous guided change with pre-commit hooks

On a similar line as the ArchUnit tests, we’ve introduced a git pre-commit hook (using husky), which runs through the touched files and verifies that certain things are not present anymore. This supports a continuous refactoring approach to things like renaming or change of tool, in the sense of a fitness function5.

For example whenever you have touched a test, all junit4 tests should be junit5 now and the name ‘OutputView’ should not appear anymore in any variable name, but be replaced with ‘View’.

Scanning through the file of a commit, the script searches for appearances of unwanted content and prints the violation to the console. Each violation has an explaining comment which is printed along-side.Violation: File Application.test.kt contains org.junit.test. Please migrate Junit4 tests to Junit5.

Summary

We looked at an approach to restructure a messy code base in five steps:

- Get a shared understanding of the business context: Bring everything on the table, share knowledge and agree on terms

- Define a high-level target structure: Define a first version of the target structure to guide further steps. Revisit it frequently.

- Name the mess: Collect low hanging fruits by moving and renaming things according to their semantic.

- Identify and prioritise the hot spots: Analyse the code base to identify where complexity lies, prioritise it according to impact on the upcoming work.

- Restructure: Limit and coordinate the more complex refactorings to stay focused. Don’t be afraid to question.

We also looked at a three tools that supports continuation of a unified vision, even if the people change:

- ArchUnit: For expressing intention and structure in form of tests.

- Manifesto / Code of Conduct: For sharing the core ideas and direction with any person unfamiliar, explicitly and brief.

- Continuous guided change with pre-commit hooks: For verifying that no unwanted content is present in any touched file, this pushes developers to apply the Boy Scout rule.

Send me some feedback on this post via Social Media.

References

1 In her book Dynamic Reteaming, Heidi Helfand calls this approach of building a new team around a specific problem Isolation Pattern.

2 Eventstorming is an approach to discover the domain in form of a workshop. We used Mural to do this remotely.

3 If you know who the origin of this analogy, please let me know.

4 See also https://www.solutionsiq.com/learning/blog-post/lines-of-communication

5 A Fitness Functions as described in the book Building Evolutionary Architecture produces a statement, which tells us if we move forward in the direction of a desired achitectural characteristic.